|

|

Nicolaus Copernicus quick facts:

|

|

Polish:

Born:

Died:

Known for:

The most famous work:

Fields of activity:

|

|

Mikołaj Kopernik

19 February 1473, Toruń

24 May 1543, Frombork

Heliocentric theory (Copernican Revolution)

De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium

Astronomy, Mathematics, Canon Law, Medicine, Economics

|

Nicolaus Copernicus - an astronomer, mathematician, economist, doctor and clergyman; an all-round Renaissance man; the greatest and most popular native of Toruń. Nicolaus Copernicus - an astronomer, mathematician, economist, doctor and clergyman; an all-round Renaissance man; the greatest and most popular native of Toruń. Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is regarded as the starting point of modern astronomy and the defining epiphany that began the scientific revolution.

Today, Copernicus is one of Toruń’s greatest assets, not only in terms of tourist attractiveness: he is an instantly reco-gnizable symbol of the city. Although he was mainly an astronomer, famous for introducing the heliocentric model of the world into modern science, he largely contributed to other fields as well.

| Life and Work |

He was born on 19 February 1473, presumably, in one of the houses in St. Anna Street (present-day Copernicus Street) at no. 15 or 17 (see the map). His exact birth location is one of the things that still remain unknown. His works, masterpiece and life have been thoroughly examined; nevertheless, there are certain facts of his life that have never ceased to raise serious doubts.

Nicolaus Copernicus was born on 19 February 1473, presumably in one of the houses in St. Anna Street (no. 15 or no. 17), renamed Copernicus Street some time ago, or in a tenement in the Old City Market Square.

Nicolaus Copernicus was born into a family of an affluent Toruń merchant, Nicolaus Copernicus Sr., who was originally from Krakow. Nicolaus and his wife Barbara had four children: Andrew, Barbara, Catherine and Nicolaus - the youngest.

Nicolaus spent his early childhood and youth in Toruń. The lively and peculiar character of the city had an enormous influence on the development of his versatile personality, in particular the foreign merchants coming to the city on business and stopping at his family house to share their observations with the hosts, arousing young Copernicus’s curiosity.

Here Copernicus started his education. He attended the city school under the auspices of St. Johns’ Church, located in School Street – now St. John’s Street. There is some evidence to suggest that the school, which itself was of high academic standards, could boast a large number of eminent professors, including Lucas Watzenrode, Copernicus’s uncle and successive patron, and a rich library with works and manuscripts in the field of astronomy and astrology. It was presumably here that Copernicus for the first time took interest in the sciences. The evidence excludes the possibility of Nicolaus Copernicus attending schools in the towns of Gniezno, Włocławek and Chełmno. At the age of 18 Copernicus began his university education in Krakow.

In 1491-1495, together with brother Andrew, Nicolaus was a student of the Department of Liberal Arts in Krakow University, an institution of high academic standards in the field of mathematics and astronomy. The enrolment checklist for the winter semester of 1491/1492 still includes the following information: "Nicolaus Nicolai de Thuronia solvit totum", which translates as “Nicholas, the son of Nicholas of Toruń, settled all dues”. It appears then that Nicolaus Copernicus paid the whole university fee as soon as he enrolled in studies.

In 1496 he undertook an astronomy course in Bologne, Italy, and in 1501 law and medicine in Padua, Italy; in 1503 he received a doctorate in canon law in Ferrara, Italy. In late 1503 Copernicus returned to Poland and settled in Varmia, instead of Toruń. In 1504-1510 he worked a secretary and doctor for Lucas Watzenrode, his uncle and the Bishop of Varmia, and spent most of his time in Lidzbark Warmiński. In 1509 he published his Latin translation of Greek letters by Theophylact Simocatta, and in 1510, as a canon and the chapter administrator, he settled in Frombork, where he did his astronomical research and wrote his most famous work. In 1516-1519 and in mid-1521 he administered Olsztyn chapter property and in 1520-1521 defended Olsztyn castle in the war against the Teutonic Order.

One of Copernicus’s interests was also economics, which in 1517 induced him to write a proposed scheme of currency reform. In 1519 he submitted an appropriate memorial in this matter during a Prussian Diet in Toruń, which was enlarged by Jôst Ludwig Dietz in 1526 and included into a treatise entitled "Monetae cudendae ratio" ("On the coin minting method "). Before that, however, in 1522 during the Prussian estates meeting in the town of Grudziądz, Copernicus presented his treatise on the Prussian coin reform, which formulated the principles of the monetary reform according to the project of money improvement and unifying the Prussian and Polish coins. He also defined an economic law which stated “Bad money drives out good”. Later the law came to be termed Gresham’s law, as Gresham was credited with discovering it. |

|

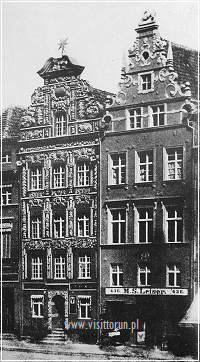

Copernicus Street (in the Middle Ages called St. Anne Street) with two Gothic houses - Nicolaus Copernicus Museum >>

Lucas Watzenrode (1447-1512), a Prince-Bishop of Varmia and patron of his nephew, the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus.

Copernicus's treatise "On the coin minting method"

|

| De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium |

|

Copernicus devoted all of his spare time to his masterpiece. In around 1510 he outlined the heliocentric theory in a treatise known as "Commentariolus", which was never published and circulated around Europe in copies. Two of them were only found in the 19th century.

Copernicus wrote his main work, "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium" (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), in Frombork in 1515-1530. It included an astronomy lecture on the Earth spinning around its axis and planets, including the Earth, orbiting the Sun. Although Copernicus never announced the results of his research, and it was only in 1535 that, prompted by Bernard Wapowski (a historian and the leading Polish cartographer), he compiled an almanac (lost) on the basis of astronomical tables from "De revolotionibus orbium coelestium", the news of the new theory spread through Europe. It reached also Georg Joachim von Lauchen (Rheticus), a German astronomer at the University of Wittenberg, who in 1539 arrived in Frombork to learn about Copernicus’s work. He admired the theory and induced Copernicus to publish the work. He prepared an excerpt of the work, known by the shortened title as "Narratio Prima", and published it in Gdańsk in 1540 and in 1541 in Nuremberg. The publishing process was supervised by Andreas Osiander, who he withdrew Copernicus preface to the work without his consent and replaced it with his own, anonymous, presenting the theory as a hypothesis facilitating calculations. It did not follow Copernicus’s theory, which was clearly defined in a letter of dedication to Pope Paul III, printed at the beginning of the same book.

The work was published in Nuremberg in 1543 under the name of Nicolai Copernici Torinensis (Copernicus always emphasized his origins adding “a native of Toruń”).

Copernicus died on 24 May the same year in Frombork and was buried in a crypt of Frombork Cathedral. His work, which challenged the accepted beliefs concerning the model of the world, was not readily accepted by scientists and church authorities. Copernicus theory, which during his lifetime met with a strong disapproval on the part of Martin Luther, Phillip Melanchton and John Calvin as contradicting the Bible, from the turn of the 17th century began to attract more and more followers. It received considerable support especially from Giordano Bruno, Johann Kepler and Galileo Galilei, who helped to consolidate it.

The Catholic Church, which initially failed to take an official stand on the theory, rejected it as potentially dangerous to the accepted model of the world after the Council of Trent. In 1616 the Congregation of the Index issued a decree condemning Copernicus’s work. However, it was removed from Index Librorum Prohibitorum only in 1758.

|

|

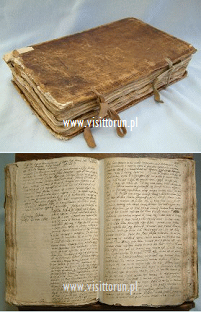

Original Nuremberg edition 1543

Manuscript of the Nicolaus Copernicus's De Revolutionibus... Heliocentric model of the solar system.

Historic editions:

• 1543, Nuremberg, by Johannes Petreius

• 1566, Basel, by Henricus Petrus

• 1617, Amsterdam, by Nicolaus Mulerius

• 1854, Warsaw, with Polish translation and the authentic preface by Copernicus.

• 1873, Toruń, with German translation sponsored by the local Coppernicus Society, with all Copernicus's textual corrections given as footnotes.

|

| The Copernican Revolution |

| (as Copernicus’s demonstration and work were referred to) rejected the presupposition dominating over centuries and shifted towards the old heliocentric model, proposed by Aristarchus of Samos. The goal was to develop sufficient scientific evidence to support the theory, as comprehensive and precise as possible within the limits of the existing knowledge. |

|

|

| Nicolaus Copernicus’s father |

– Nicoalus Copernicus Sr. (Copernigk Niclas; ca. 1420-after 1483) – was a Krakow merchant, who belonged to Toruń and Krakow Company of the Sweydniczers and moved to Toruń before 1458. Supposedly, his family branch originated from the village of Koperniki in Silesia.

In Toruń Nicolaus Copernicus married Barbara Watzenrode of an affluent patrician family and had four children: Andrew, Barbara, Catherine and Nicolus. He maintained trade contacts with Krakow, Gdańsk and other cities. In 1465-1483 he was an Old City of Toruń juror and in 1469 he and his wife became members of the community of tertians of the Dominican Monastery. |

|

Nicolaus Copernicus Sr., 17th-century painting

|

| Nicolaus Copernicus – A German or a Pole? |

A German or a Pole: here is the question that is central to the dispute between the Polish and German scientists. Both try to convince of the astronomer’s Polish or German roots respectively. His origins have been investigated through a careful examination of archive documents and letters for decades.

It seems, however, that he was neither. He was above all a loyal subject to the King of Poland and a native of Toruń. The very idea of national identity was unheard of at the time and the emphasis was on the serfdom and the place of origin.

Nicolaus Copernicus’s mother, Barbara Watzenrode, was most likely Westphalian, as were a large number of other 13th- and 14th- century new arrivals to Toruń (more on the first inhabitants of Toruń read here). Here, the family soon became part of the patrician class. According to other evidence, the family had their roots in Krakow (in particular astronomer’s father), as this is where they moved from Silesia.

Whatever his descent, Nicolaus Copernicus had an excellent command of German and Latin. He may have known some Polish and some Italian as well since he spent 10 years in Italy studying. However, none of his written work is in Polish and it is by no means certain certain he knew the language.

Most historians agree that the family used German at home, which, however, cannot constitute a convincing argument. At the time two languages were used in Toruń: the same name could be registered both in Polish and German in various documents and both languages were used on the street. Secondly, the idea of ‘patriotism’ or national identity did not exist. What mattered was the loyalty to a monarch and Copernicus owed allegiance to the Polish King, which he repeatedly demonstrated by, for example, defending Olsztyn castle against the Teutonic Order. Moreover, the inhabitants of Royal Prussia, the autonomous province of the Kingdom of Poland established after the Second Peace of Toruń in 1466 dissolving the Tetonic State, with Toruń as one of the most important and largest cities, demonstrated strong ties to the province, and even if they were speak of their national identity, they mentioned Royal Prussia in the first place.

|

|

|

| Nicolaus Copernicus of Toruń |

Nicolaus Copernicus numerously emphasized his Toruń origins and was proud of the Great City of Prussia with a large legal and political autonomy, where he came from. In the album of scholars of Krakow University in 1491 he matriculated as "Nicholas, the son of Nicholas of Toruń". On the title page of "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium", his greatest work written in Latin, he added a meaningful nickname of "Torinensis" (a native of Toruń) to his name and surname. Similar notes appear in some of his other writings.

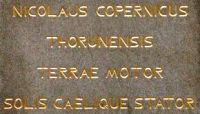

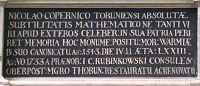

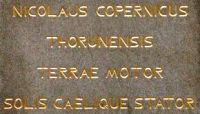

Thus, undoubtedly, Nicolaus Copernicus was from Toruń. The fact was also aptly underlined by Rudolph Brohm, a professor of Toruń Gymnasium and the author of the Latin inscription on the pedestal of Copernicus monument erected by the Germans in 1853, which says: "Nicolaus Copernicus Thorunensis, Terrae motor, Solis Caelique stator" (Nicolaus Copernicus of Toruń, moved the Earth, held the Sun and heaven). Although he was German, he did not pronounce Copernicus German.

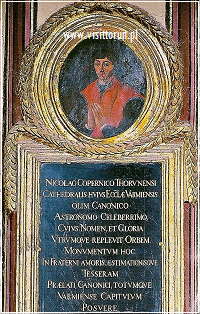

A similar bond between Copernicus and Toruń was emphasized by Nikodem Frischlin (1547-1590) in a rhymed laudation on Copernicus, included for the first time in the "Icones" by Nicolaus Reusner, a collection of the sketches of scholars, published in Strasburg in 1587. The praise is also included in the Renaissance epitaph on Nicolaus Copernicus in Toruń cathedral. |

|

Fragment of the title page of "De Revolutionibus..."

Fragment of the Copernicus-dedicated epitaph, around 1580, in the Cathedral of Toruń

Inscription on the monument to Copernicus |

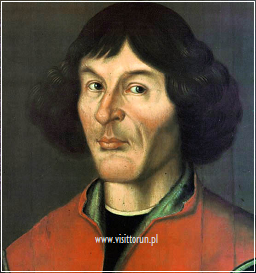

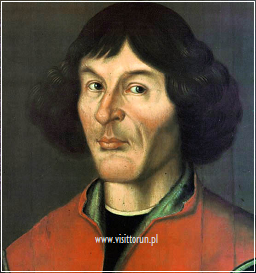

| What did Nicolaus Copernicus really look like? |

|

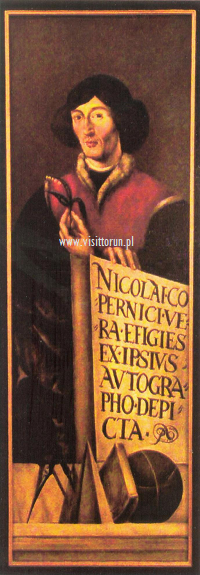

An authentic portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus existed in the 16th century, painted by the astronomer himself. As befitted a true man of Renaissance, beside a number of other skills, Copernicus was also accorded a painterly talent. After his death, the portrait became the property of the Chapter of Varmia and in 1584 a gift to Tycho de Brahe, a Danish astronomer, who admired and respected Copernicus. Thus, the portrait was brought to the Danish island of Hveen, where Brahe had his castle and astronomical observatory. The portrait and the castle were destroyed in 1597 by Brahe’s enemies.

There is some evidence, however, that the portrait had a copy.

Before 1580, in Strasburg cathedral a famous astronomical clock was made, based on the Copernican system. Beside the clock, in the tower, a Nicolaus Copernicus’s portrait was placed, depicting the astronomer as standing and holding a lilly of the valley in his left hand, while the right one was resting against a plate with a Latin inscription which translates as: "A true image of Nicolaus Copernicus, painted after his self-portrait". The copy had been made by Tobias Stimmer, which had not been confirmed until 1873, when an unexpected discovery of an inscription on the back of the painting was made. It said: "Nicolaus Copernicus portrait copied by Tobias Stimmer according to the original, which doctor Tidemann Giese sent to Dasypodius from Gdańsk".

Before 1550, Bishop Giese of Chełmno sent the aforementioned portrait to Dasypodius in Strasburg, who was working on the mechanism of the clock. Stimmer made the copy and the portrait returned to Frombork. In 1584 it was presented to Tycho de Brahe.

Tobias Stimmer made also a wood-engraved portrait of Copernicus, included in "Icones seu immagines virorum litteris illustrium" of 1587, comprising one hundred portraits of eminent scholars. The astronomer is depicted almost identically, with a lilly of the valley in his hand.

The wood-engraving later served as a model for making a copperplate by Jan Teodor de Bry, published in 1593 in the "Images of Distinguished Scholars Famous for Their Knowledge and Erudition". It bears a Latin inscription saying: "Nicolaus Copernicus Thornaeus Borussus Mathematicus" ("Nicolaus Copernicus a native of Toruń and Prussia, and a Mathematician”).

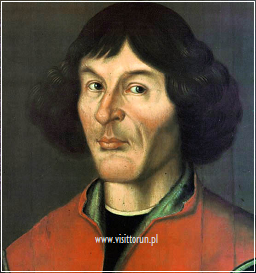

Today the most popular is the so-called Toruń portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus, included in numerous reproductions. It was made in 1585 and hung in the library of the Academic Gymnasium in Toruń (read more: Copernicus-related memorabilia here).

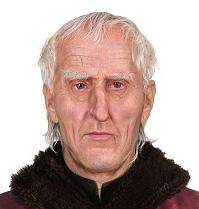

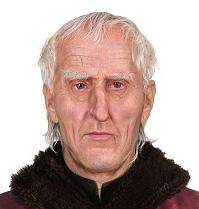

The archeological works carried in autumn 2005 in Frombork cathedral led to the discovery of, as was eventually established, Nicolaus Copernicus’s remains. The scull found in the tomb was used to reconstruct Copernicus’s image at the age of 70. The computer visualization bears some resemblance to the most popular portrait of the astronomer – the so-called Toruń portrait.

The skull and, in particular, the nose, are deformed. Similarly, the surviving portraits show Copernicus’s broken nose and the slightly deformed left side of the face. It is also possible to ascertain that between the age of seven and twelve Copernicus suffered from an accident.

|

|

The oldest known picture of Nicolaus Copernicus by Tobias Stimmer, 1574-79, the astronomer as standing and holding a lilly of the valley in his left hand, while the right one was resting against a plate with a Latin inscription which translates as: "A true image of Nicolaus Copernicus, painted after his self-portrait".

Tobias Stimmer, 1587, woodcut of Copernicus published in Nicolaus Rausner's work "Icones seu imagines virorum literis illustrium" (Images of Distinguished Scholars Famous for Their Knowledge and Erudition)

Sabin Kauffmann, 1600: woodcut modeled on the work of Thobias Stimmer

The reconstruction attempt using the discovered skull of Copernicus |

| Where was Nicolaus Copernicus really born? |

Today Copernicus’s House-Museum is located at 15-17 Copernicus Street, which at the time of his birth bore the name of St. Anna Street. It comprises two Gothic tenements, one of which belonged to the Copernicus family. Supposedly, Nicolaus was born at no. 15, as the tenement was the property of Copernicus’s father in 1464-1480. Here, presumably, the astronomer also spent the first 7 years of his life.

However, the fact that Nicolaus Copernicus was born precisely here is by no means certain.

Recently, much attention has been directed to one of the tenements in the Old City Market Square, which once belonged to the Copernicus family. It was demolished in the 19th century and replaced by the present-day department house in 1896 (>>). Several years ago some historians postulated that Nicolaus Copernicus was born in this tenement rather than the one in present-day Copernicus Street. One of the arguments to support the hypothesis was that the former was far more imposing than present-day Copernicus house.

Considering lack of any sources relating to the Copernicus family in 1468-1480, the astronomer’s exact birthplace is difficult to establish and, therefore, the present-day Copernicus house has been accepted as one.

Similarly, there is no evidence to suggest where his older brother Andrew and his two sisters, Barbara and Catherine, were born.

The lack of evidence and imprecision concerning Copernicus are strictly related to the centuries-long oblivion of the astronomer, who had his revolutionary work included in the Index of Forbidden Books. The old-time interest was revived as late as the 18th century, following a growing interest in mathematics, natural sciences and astronomy. In 1711, Jacob Heinrich Zernecke, a famous Toruń chronicler, was the first to postulate that Copernicus was born in the “corner house not far from the Old Toruń Gate". In 1740, Samuel Luther Geret (last Toruń Burgomaster before the Partitions of Poland) put forward another hypothesis saying that the inconspicuous corner tenement (still Gothic and not rebuilt then) at 30 Copernicus Street (the corner of Piekary Street) was the astronomer’s birthplace. To mark his discovery, he had a wooden occasional pyramid built over the well in front of the house, at the top of which he placed a globe. In the time of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), the commanding officer of the fortress of Toruń, General Woyczyński, had a memorial brick taken out of the building. He sent it to Duchess Izabela Czartoryska in the town of Puławy, who placed it in the Temple of Sybille – the first Polish museum. The tenement, considered to be the astronomer’s birthplace was also visited by Napoleon in 1812 and 15-year-old Frederic Chopin in 1825. Here a commemorative plaque was placed in 1872 (see "Copernicus-related memorabilia" here). In 1881 careful archival research undertaken by historian and Toruń Burgomaster George Bender pointed to present-day Copernicus House in Copernicus Street as the astronomer’s birthplace. |

|

Two Gothic patrician houses at 15-17 Copernicus Street which once used to belong to the Copernicus family. The one to the left (at No. 15) is supposed to be the birthplace of Nicolaus Copernicus. Today both houses compose Copernicus House Museum.

The Lion patrician house at 36 Old City Market Square (the one to the right) was completely remodelled in the early 20th century. In the Middle Ages it belonged to the Copernicus family. Many historians are of the opinion that Nicolaus Copernicus was born here.

Click to enlarge

|

| Where is Nicolaus Copernicus’s real burial site? |

In the 18th century an incorrect theory concerning Copernicus’s burial site spread and established in Toruń for a long time. The theory, postulating that the astronomer was not only born in Toruń but also died here, was largely popularized by Toruń scholar Samuel Luther Geret. In his work entitled "Fragments of Thought and History" published in 1783 in Winterthur he proposed that Copernicus was Toruń parish priest and it was here, rather than Frombork, that he died and was buried. The theory prevailed also in 1841, when Adam Mickiewicz (Polish great Romantic poet) in his lectures on Slavonic literature in French College in Paris claimed that „upon receiving the position of a canon in Toruń, Copernicus settled in the city, died and was buried there”.

Today it is clear that Copernicus died in Frombork, where he settled in 1510 and became the administrator of the Chapter of Varmia. He was buried in a crypt of Frombork cathedral, by one of the side altars. His tomb was discovered and confirmed through archeological works in 2005 and DNA research, which unraveled the mystery of his burial site. |

|

The 18th-century Copernicus-deditated epitaph in the cathedral of the town of Formbork

|

| Copernicus-related memorabilia |

The first and most significant place relating to Nicolaus Copernicus is St. Johns’ Cathedral in Toruń and, in particular, the side Chapel of Guardian Angels, also known as Copernican. The centre of the chapel is occupied by an early-Gothic baptismal font, in which Nicolaus was baptized in 1473.

Toruń revered Copernicus’s memory as early as the Middle Ages, even though his fame reached his home city more than a dozen years later. The first memorial in honour of the astronomer was a symbolic epitaph founded by Toruń doctor and humanist Melchior Pirnesius in 1589, placed in the Chapel of Guardian angels in St. Johns’ Cathedral. The epitaph, bearing the astronomer’s portrait modeled on his ‘true’ image from the solar clock in Strasburg Cathedral tower, is still available for viewing in the cathedral. The famous Strasburg portrait is currently the oldest surviving image of the eminent scholar, painted around 1574 by Tobias Stimmer.

The epitaph in St. Johns’ Cathedral in Toruń shows Copernicus bust facing right, his hands clasped in prayer, in a soutane and a red vestment. The background depicts a chamber interior with a window view of a hummocky landscape, accentuated by a large cross in the foreground. In the top right corner there is a shelf with an astrolabe and a pair of compasses. The bottom right bears a Latin inscription which translates as "I am not seeking grace similar to that of St. Paul, nor forgiveness St. Peter was granted; only for the forgiveness you gave the sinner on the cross do I incessantly beg”. According to a Latin inscription on the frame, the epitaph was founded to honour Copernicus and “…not let the memory of such an eminent man escape his homeland as he is surrounded by the greatest glory abroad…”.

A similar - though somewhat more modest - memorial of Nicolaus Copernicus is the other of his two old portraits – the famous Toruń portrait of 1585 that used to hang in the Academic Gymnasium in Toruń. The painting presents the bust of the astronomer around the age of 40, in a red sleeveless garb lined with fur over dark clothes. The outstanding north-European work of art is anonymous although some scholars attribute it to Flemish painter Marcus Geeraerts. Today the painting is exhibited in the Old City Town Hall Museum, with the copies hanging in Nicolaus Copernicus Museum and the office of the Nicolaus Copernicus University president.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw the period of reduced interest in Copernicus, being the result of including his work "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium" in the Index of Forbidden Books. In view of the fact, particularly noteworthy was the foundation of a modest marble bust of Copernicus in 1766 by Prince Alexsander Jabłonowski, a governor of Nowogródek, made by Krakow sculptor Wojciech Rojowski. It is the . Owing to its little value, it was held in the Old City Town Hall hidden from public attention, by order of the City Council, despite the founder’s suggestion to place it in the north part of the Old City Market Square. Around 1780 Duchess Izabela Czartoryska made attempts to obtain the bust for the museum being established in Puławy at the time. It was not moved to the (Copernican) Chapel of Guardian Angels in St. Johns’ Cathedral until the early 19th century, where it is currently available for viewing.

Erecting the imposing Copernicus Monument in front of the south-east corner of the Old City Town Hall in Toruń was the initiative of the State Council of the Duchy of Warsaw, which laid the cornerstone for the monument during the session held in Toruń in 1809. The project was implemented much later, in 1853. More on the monument here.

In 1871 a scientific society known as Coppernicus-Verein für Kunst und Wissenschaft (Copernicus Association for Art and Science) founded a commemorative plaque in German, placed on the wall of the alleged house of Nicolaus Copernicus at 40 Copernicus Street, to mark his birthplace (in 1812 the house was visited by Napoleon and in 1825 by Frederic Chopin). By doing so, they physically and publicly pronounced the wrong house the birthplace of the great astronomer, allegedly born in the 18th century, which was a mistake. 10 years later the mistake was discovered and removed by Burgomaster Bender, who conducting archival research confirmed that Copernicus house was located at 17 Copernicus Street. In 1923, on Nicolaus Copernicus 450th birth anniversary, a Polish commemorative plaque was unveiled there. The German plaque was not removed from the wrong house until 1933, when the preparations to the 700th anniversary of granting Toruń its city charter began. It was stored in a museum for several years and in 1939 Germans restored it to its former position. In 1945 they took it back to Germany and removed the Polish plaque from the house at no. 17.

Nicolaus Copernicus’s 400th birth anniversary in Toruń was celebrated at two events in 1873: the Polish celebration organized by the Society of Moral Interests and the official German one held in Artus House, the Old City Town Hall and the Academic Gymnasium. The Polish celebration was to be distinguished by the exhibition of Jan Matejko’s portrait of the astronomer in Toruń. However, Krakow authorities decided to keep the portrait in Krakow to mark their own anniversary celebration. Today the work is hanging in Jagiellonian University Museum in Krakow. Nonetheless, Toruń celebrated the anniversary by publishing the astronomer’s biography and an illustrated book of his monuments and portraits, as well as by minting a commemorative medal. In the newly-erected building of the Learned Society of Toruń, Copernicus bust found its place among a collection of plaster busts of Polish monarchs and other famous Poles presented to the Society.

In 1923, on Copernicus’s 450th birth anniversary, another commemorative plaque was unveiled, this time at 17 Copernicus Street. In 1939 it was hidden from Germans to wait for the end of the occupation and was restored to its former place after the war. However, in 1960 a beautiful Gothic fronton was discovered under the plaster on the façade of the tenement. When the renovation commenced, the plaque was removed and placed in the local museum. The inscription on it says "Nicolaus Copernicus was born here on 19 February 1473. A native of Poland, he held the Sun and moved the Earth".

Beside paintings being the manifestation of reverence of great Toruń astronomer, particularly noteworthy are the editions of his masterpieces, including the three oldest printed in Nuremberg in 1543, and several old prints in the collections of Copernican Library and Copernicus Museum, describing the development of his work.

After World War II, Copernicus memory was honoured in a variety of ways. Following the decree of the State National Council of 14 March 1945, Nicolaus Copernicus University (>>) was established in Toruń, turning it into an important academic and cultural centre.

In 1973, the Council of Ministers introduced a bill appointing Toruń a venue for celebrating Nicolaus Copernicus 500th birthday anniversary. As a part of preparations to the event, a number of permanent investments were made in the city, the most important being the restoration of the Old Quarter monuments, especially those remembering Copernicus early life, through appropriate conservation work. Moreover, the NCU campus was erected in the area of Bielany, in form of a uniform student city with several Copernicus memorials, such as, for example, a sculpture in front of the main hall resembling his book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, a composition made of the sky, Copernicus portrait and the solar clock on the auditorium wall, and a copy of the astronomer’s portrait in the President’s office, taken from the Academic Gymnasium.

The astronomer’s family house, renovated in 1960-1963 and in 1972, became Copernicus Museum. In the year 2000, on its 40th anniversary, the museum received a precious gift: the Amsterdam edition of "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium" of 1617. In 1973 in Rapackiego Square, a monument in honour of Copernicus was erected, representing the idea of Copernicus System, while in the Polish Home Army Square a spatial construction was built in memory of his discovery. It was demolished in 2006.

The celebrations also contributed to the improvement of Toruń tourist base: several new gastronomies and hotels were opened; the Philadephia Boulevard was built along the Vistula, together with the recreational fields stretching beyond the boulevard; the new building of Copernicus Library was erected; and the transport infrastructure was improved. Similar large-scale investments relating to Copernicus’s birth anniversary never happened in Toruń again.

A peculiar Copernicus-related memorial, referring to the 8th page of his major work and modeled on his heliocentric system is the Cosmopolis Fountain (>>) of 2008.

|

|

The 16th-century Copernicus-deditated epitaph in the cathedral of Toruń. Click to enlarge

The Toruń portrait of Copernicus from the 16th century is one of the most precious memorabilia relating to Copernicus. It can be seen in the Old City Town Hall in Toruń

The 1766 bust of Copernicus in the Toruń cathedral is the world’s oldest monument of Nicolaus Copernicus

.bmp)

Monument to Copernicus in Toruń, 1853. Click on the picture to read more.

Copernicus painting by Jan Matejko, 1873. Click to enlarge

Copernicus birthlplace commemorative plaque

Decorative panneau dedicated to Copernicus on the facade of the Nicolaus Copernicus University's main auditorium hall in Toruń, 1973

Monument to Copernicus's "De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium" in the university campus in Bielany district

Monument in honour of Copernicus, representing the idea of Copernicus System, 1973

Cosmopolis fountain |

Related links: Related links: .bmp) Copernicus House Museum here Copernicus House Museum here .bmp) Copernicus Tour here Copernicus Tour here .bmp) Cosmopolis Fountain here Cosmopolis Fountain here .bmp) Astronomy Observatory here Astronomy Observatory here .bmp) Nicolaus Copernicus University here Nicolaus Copernicus University here

|

Curent local weather in Toruń  | temp. 7.3° C |

|

Nicolaus Copernicus - an astronomer, mathematician, economist, doctor and clergyman; an all-round Renaissance man; the greatest and most popular native of Toruń.

Nicolaus Copernicus - an astronomer, mathematician, economist, doctor and clergyman; an all-round Renaissance man; the greatest and most popular native of Toruń.  Related links:

Related links:

.jpg)

.bmp)

.bmp)